Dear Jonas,

Yesterday we went to see the Elizabeth Peyton show at the New Museum. Your dad says you fell asleep shortly after seeing the Johnny Rotten portrait. Since your Dad could be a sort of handsome John Lydon, I guess that makes sense. Maybe the pinks and oranges felt familiar. If so, I think her paintings worked on you in the same way they arrested me: their obsession with fey, arrogant beauty is one with which I am familiar.

Reviews of Peyton’s work often describe her colors as “gem-like,” but her palate is totally Ziggy Stardust’s androgynous make-up box: kabuki exotica sharply blended over pallid junkie foundations. The obviousness of the colors—chartreuse, carmine, indigo—denaturalize her subjects and lend them their emphatic beauty. The impossible glamour is underlined by the fact that viewers can’t always be sure of which of Peyton’s subjects are people she knows and which are people with whom she has fantasized a relationship, a move that destabilizes their relationships to copy and original. The eyes of each painting seduce, reach out, and reassure the viewer with a very pretty urgency: your desire is not impossible, or, to quote Lady Stardust: “Oh no love, you’re not alone!”

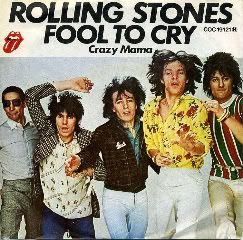

Her work is successful in the way that young adult fiction by Francesca Lia Block, or films by Sofia Coppola and Wes Anderson are not. Whereas these people often have the necessary ingredients for glittery preciousness, the end result is almost always cloying and self-congratulatory. Peyton’s small squares promise a captivating, actually existing, world of aristocratic common people where beauty is a generative response to beauty. Like Todd Haynes, Peyton renders a process of desire visible. There is a queer argument to this exhibit that is keenly exposed by “E.P.’s” self-portraits in which she may as well be one of her young male sylphs: become what you want. As contemporary queer theory has shown, this is entirely possible but with the permanent caveat of subjection: we cannot exist without context, without history, without other, and in this sense Lady Stardust’s advice is also practical and contemplative—autonomy is impossible. I had the sense that, had E.P. begun her career a bit later, there would be more of an “all the young dykes” feel in place of all the young dudes. I hadn’t before put the current trans-aesthetic in line with the history of hot androgynies Peyton has curated, but I think a link might be drawn. In any case, there is a consistency of gaze and figure throughout the entire collection that underscores the fragile ways we own our attractions—what is it that all of these objects have in common? What exactly is the desire that Peyton has isolated through this work? Looking at the portrait of Keith Richards somehow made the million times I've watched Gimme Shelter make sense. Perhaps the show’s title offers one explanation: “Live Forever.” Of course vampires are the only ones who enjoy this privilege—vampires and anyone beautiful enough to make their way into one of these paintings.